From 'We can do it' to the drawbridge: Europe’s migration shift since 2015

After more than a million arrivals in 2015, European states have tightened borders, struck external deals and reshaped asylum policy, leaving island communities wary of another surge.

European governments that once embraced a message of welcome have reshaped their migration policies in the decade since 2015, erecting new controls, negotiating external agreements and tightening asylum rules to curb arrivals.

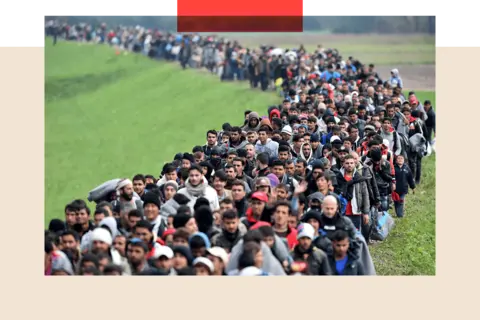

More than a million people crossed into the European Union in 2015, driven largely by conflict in Syria and instability in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere. The influx overwhelmed reception systems in several member states and prompted a political backlash that contributed to a hardening of national positions on migration across the bloc.

Local communities that helped during the emergency have mixed memories of those months. Paris Laoumis, a hotelier on the Greek island of Lesbos, recalled assisting exhausted asylum seekers on beaches in August 2015 and said he was proud of the solidarity shown then. But he and others on the islands now say the landscape has changed and worry that another surge of arrivals could test current systems.

Within months of the 2015 peak, European capitals moved to reduce arrivals by strengthening external borders, accelerating returns and seeking agreements with third countries to limit onward movement to EU territory. The 2016 EU-Turkey agreement, which aimed to reduce sea crossings from Turkey to Greece, became a defining example of the bloc’s new approach to managing migration flows.

Those measures were accompanied by operational changes at the EU level, including a stronger role for border agency Frontex, expanded screening and registration procedures at arrival points, and the creation of so-called hotspots to process people arriving irregularly. Member states also revised asylum procedures, and some introduced faster returns or more restrictive criteria for protection.

The political consequences were immediate. Governments that had welcomed refugees faced public debate and electoral challenges, and migration rapidly became a central theme for parties across the continent. Right-leaning and nationalist parties gained influence in several countries by campaigning on border control and migration limits. These shifts at the ballot box, in turn, influenced national policies and helped produce consensus in some capitals for tougher measures.

Aid groups and human rights organisations have frequently criticised the new policies, saying external deals and tightened border controls have shifted the burden to transit countries and increased risks for people on the move. Concerns have included the conditions in reception centres on the Greek islands, the treatment of those returned to non-EU countries, and reports of pushbacks at sea or on land at some EU borders.

Officials who support robust border measures argue that controlling irregular arrivals is necessary to maintain orderly asylum systems and public support for refugee protection. They point to reductions in crossings after 2016 and to the need for variables such as security checks and registration to be robust to prevent exploitation of asylum systems.

The migration landscape is not static. Flows have been shaped by geopolitical events, shifting conflict zones, seasonal patterns and the capacity of routes through the eastern Mediterranean, central Mediterranean and western Balkans. Policy changes in Turkey, Libya and North Africa, as well as efforts by EU countries to cooperate on policing smuggling networks, have affected the numbers and routes used.

Local authorities and volunteers who responded in 2015 say they remain vigilant. On Lesbos, the beach that was once a regular landing point is now quiet, but residents recall the strain on services and the emotion of those months. Some warn that renewed instability in parts of the Middle East and Afghanistan, combined with tightened legal routes for migration, creates conditions in which irregular crossings could increase again.

At the EU level, debates continue over how to balance externalisation of migration control, solidarity between member states and compliance with international asylum obligations. Proposals have ranged from mandatory relocation schemes and faster asylum procedures to expanded partnerships with transit countries and stepped-up returns. Implementation has been uneven, reflecting political divisions among member states and legal challenges.

A decade on from Chancellor Angela Merkel’s 2015 declaration that "we can do it," the policy consensus in Europe has decisively shifted toward containment and external cooperation. Governments and communities that experienced the arrivals of 2015 now say they have rebuilt reception capacity and tightened processes, but they also say preparedness remains essential should crossings rise again. The debate over how to reconcile border management with humanitarian obligations is likely to remain central to European politics in the years ahead.